The First Russian Women’s Ascent of an Elite Free Climbing Route

Ekaterina Matyushevskaya

The first Steel Angel award winner (2008) and the Steel Angel award winner in the 2014.

Irina Morozova

Co-author and co-founder of the “Steel Angel” award.

The Lifetime Achievement Steel Angel Award (2016)

She first ventured into the mountains in 1987.

In 2006, she made her first ascent as part of a women’s duo, and by 2008, she became the ideological leader of women’s mountaineering in Russia.

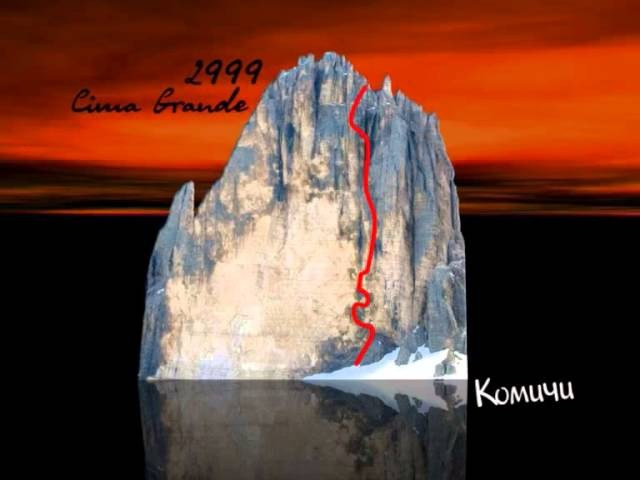

Route “Comici” on Cime Grande di Lavaredo

5.10c, UIAA VII, all free climbing, ED

Technical Route Length: 600 m

Average Angle: Entire route — 90 degrees

Key Section Angle: 100 degrees

The peculiarity of the routes on the north face of Cima Grande is that after the first three pitches, it becomes very challenging to retreat. The middle section of the route — about 200 meters of technically demanding climbing — includes significant overhanging sections, such as roofs and overhangs. On these overhangs, the horizontal projection (the wall’s trajectory from the support point) can reach up to approximately 30 meters.

The north face ascent via the Comici route was accomplished by a women’s duo before the summer season, in early June, when snow still lay beneath the wall, in harsh weather conditions (temperatures below zero, strong winds, low cloud cover). On the day of the ascent, the meteorological data reported a temperature of minus 3 degrees Celsius.

After completing seven overhanging key pitches (R2-R9), the upper part of the route (sections R9-R15) was found to be covered in verglas.

The route was climbed in a light alpine style without the use of aid even on ice-covered sections, with the leader free climbing the entire route. The second climber also ascended the route by free climbing.

In July-August, in warm weather, the route is typically climbed in 8-10 hours. In cold weather and in the off-season, the ascent usually takes two days with a bivouac on the wall. The women completed it in one day, in 14 climbing hours.

The team did not bring aid climbing equipment, as this style of ascent is not favored in Europe. They also didn’t bring crampons to save weight, allowing the second climber to climb instead of jumaring.

The route is littered with old pitons, but these serve more as historical artifacts than reliable protection. Many of them were likely placed by Comici himself. They used their own cams and nuts for protection.

For a possible emergency bivouac, they carried minimal necessary gear — a small stove, water, snacks, an inflatable pad, a cover, and warm clothes.

Before climbing the Comici route on the north face, the duo made warm-up ascents on Torre Preuss (2700 m) via the “Little Cassin” route, VII-, 250 m, and on the summit of Cima Piccola di Lavaredo (2857 m) via the “Spigolo Giallo” route, VI, 340 m.

Story by Irina Morozova

The first warm-up route was “Little Cassin” on Cima Piccolissima (Torre Preuss), the easternmost and lowest tower in the Lavaredo massif, but with the most even and vertical wall on its south side. The line turned out to be stunning. 400 meters of vertical wall with several dizzying traverses. Describing the entire route is pointless. Those who have climbed it know it. And for those who haven’t — it’s better to climb it once than read about it ten times.

The descent from Torre Preuss was even more impressive, especially as we climbed in fog that day. At first, it was a bit unsettling to plunge into the narrow 150-meter canyon between two steep, dark, water-slick walls. The sound of falling rocks echoing into this abyss added to the suspense. But once we rappelled inside, the exotic descent in the fog, with slanted rappels on slick walls, streams, cornices, overhangs, and other delights, became reminiscent of a thrilling ride.

The next planned route was “Spigolo Giallo” on Cima Piccola. A vertical line along the southern arête, ascending to the sky like a phallic symbol. Intense, powerful male climbing in inner corners with overhangs alternated with pleasant, meditative, graceful, and airy female climbing.

On the rest day I go to Misurina, to “Lavaredo Sport” to see Giovanni, our indispensable consultant for all matters, who has worked as a guide for 40 years and knows the area like the back of his hand. I ask him about the weather forecast. He looks it up online and tells me that tomorrow will be very cold, with a night frost down to -3°C, cloudiness but no rain, while the day after tomorrow it will rain, and the weather will deteriorate significantly.

So, it’s either tomorrow or never.

I tell Gianni that we plan to climb Comici and ask for his advice on whether we can go tomorrow. He replies that it will be very cold, but okay, he would go. The day after tomorrow, however, is not okay.

Well, the local guru’s blessing is received. But what “very cold” means in the hot Italian Alps, we later appreciated as connoisseurs appreciate aged wine.

We wake up in the morning. We have breakfast with our favorite cheese, the stinkiest in the store, with green mold mixed with some slime, which no one else ate except us. But on this cheese, you can work all day, like on an energy drink.

We started early. The cold was felt immediately. After the first two pitches, Katya realized that we had accidentally taken a different route and was almost about to climb an 8a section, but stopped in time. So I had to rappel back diagonally to get back onto our line. At one point, there was a strong temptation to descend while it was still possible. But we quickly agreed to keep going to the end.

Further, there were no more ways of retreat, so everything immediately became significantly simpler. When you take a step beyond which there is no way back, all thoughts and doubts disappear, leaving only the need to move forward.

My mind was entirely focused on one task: to climb the wall before dark. There was neither the mental strength nor the desire to linger at a belay station and marvel at the breathtaking view of the vast vertical walls surrounding us—looming on both sides, plunging deep below, and soaring high above. Just a brief glance around, and my brain took a mental snapshot, capturing the image to later savor when safely on the ground, without any need to rush.

That day, I didn’t check the time once, unlike my usual habit on a route to gauge our progress. Though I was tempted to look, especially when the sun started breaking through the dark clouds that had hung over our heads all day, enhancing the gloomy atmosphere of the walls of Cima Grande and Cima Ovest on either side. The sun’s appearance on our side of the wall indicated that evening was approaching.

But checking the time wouldn’t have helped. Calculating time or not—there was no turning back. So there was no point in getting anxious by looking at the time and calculating whether we had enough of it. Besides, there simply wasn’t time for those calculations.

Especially after we completed the seven crux pitches and emerged onto what we thought would be an “easy” part of the route, expecting to move faster. But we realized that “faster” was not an option, and it would actually take longer. The fourth and fifth-class sections ahead were covered in verglas.

So, after the crux, it turned into real figure skating, except this “figure skating” was on vertical rock in climbing shoes.

And towards the end, Comici decided to test us, or rather, to check if girls have the courage. Just as we were starting to relax, thinking we had only one pitch left before the described “delicate traverse on stoppers over a roof, ” where we would need to push hard one last time, followed by another easy pitch to the main terrace of Lavaredo. And then, suddenly, we hit a black narrow chimney with a ledge, the smooth walls of which were completely covered with a layer of ice.

— Are we sure this is the way? — Mmm…—I peered around the corner, examining the surrounding walls on the right and the massive 28-meter roof, under which the traverse runs, on the left, —well… it seems there are no other options.

And indeed, there were no other options—no way to go left or right, and descending was not an option either. So we had to climb through. How? God knows. Silently. Or rather, not entirely silently. But that’s behind the scenes.

Next was the “delicate” traverse, which, after the delicate “figure skating, ” seemed not delicate at all, but, oh joy! —climbing on dry ledges and holds.

And there it was, the incomparable feeling of freedom, when we finally emerged onto the main terrace of Lavaredo, escaping from the trap where there was no choice, only one way—upwards.

Immediately, all the mental tension of the past 12 hours dissipated. There was an indescribable lightness and relief. We could put on our boots without worrying they would fall into the abyss. We could finally check the time. We could even try to call and let someone know we were okay. On the wall, there hadn’t been a thought or time to get out the phone or radio.

Another hour passed as we made our way across the terrace. Although wide, it was sloping, with icy scree and hard firn, and we were experiencing the effect of mental relaxation after “breaking free, ” so, understanding the risk of a careless move, we proceeded simultaneously with intermediate protection. We turned the corner onto the western part of the terrace.

Here, we were delightfully greeted by the setting sun, appearing in all its glory in the now-clearing sky. It was as if the clouds had waited for us to climb the wall, hanging all day as a dense dark curtain, adding to the ominous surroundings and making us nervous that they might unleash rain and thunder at any moment.

Checking the time, it was already half-past seven in the evening, meaning we wouldn’t descend before dark. And we didn’t know the descent route. Unlike the logical straight vertical rappels from Torre Preuss and Cima Piccola, the descent from Cima Grande is through southern couloirs and “gardens.” And if you haven’t scouted the descent route from bottom to top in advance, which we hadn’t, it’s tricky to navigate.

Then began the search for the right couloir, of which there turned out to be four, all with huge cairns on either side. Almost an hour was spent searching for the rappel ring that was supposed to be there according to accounts. In the remaining half-hour of daylight, we managed to rappel three pitches to the end of the couloir. While Katya descended, I used the last light to climb down the ledges and find the right gully. There was just enough twilight to locate it, and then we began descending in the dark.

Women’s mountaineering in Russia

Высотные достижения женщин в 2022. Наталья Белянкина — «Снежный барс»

Лонг-лист «Стального ангела — 2022». CrazyCats на Манаслу

2025 Nominee: Karma. First ascent of the Iris Peak in the Miyar Valley

И снится нам не рокот камнепадов, а… тропинка в Севастополь

Nominee 2025: Sourire Kirghize route. Free Climbing in Karavshin

Karavshin. Where Dreams Come True

Open Alpine Cup between an all-female team in the Caucasus

The First All-Female Ascent on Chegem Peak’s NE Face via Forostyan Route, 6A

Ася Кукушкина и Даша Ковалева прошли маршрут Горина 5А на Цей-Лоам

Маршрут Андреева 5А на Коазой-Лоам свободным лазаньем

Женская команда из Воронежа прошла маршрут Горина 5А на Цей-Лоам

Perestroyka Crack свободным лазаньем