First ascent of the Iris (5200 м), Karma route

1100 m: 650 m 6c, ED + 550 m PD/AD

- Difficulty: 6с, ED

- Length of technical sections: 650 м

- Total length: ~1100 m

- Style: The route was completed by leader free climbing. The other members followed on jumars with a heavy haul bags since bivouac gear was needed. At some pitches the team used the practiced simultaneous climbing Krasnoyarsk-style for speed.

The Indian expedition was composed of two teams: a quartet of women—Olga Paducheva, Oksana Kochubey, Nadezhda Pilschikova, and Nadezhda Muzhikina — and a male trio — Evgeny Murin, Andrey Panov, and Ilya Penyaev.

The female team’s initial objective was White Sapphire (6,040 m) in the Cerro Quistvara region, which had remained closed for many years due to the conflict between India and Pakistan. Although Kishtwar was opened to climbers in 2017, it was closed again this year, forcing the team to change their plans and seek an alternative objective. The team members themselves share the details of their story below.

Olga Paducheva:

Unfortunately, we lost many days of good weather while we were trying to get to any climbing area. First, the police turned us away from the Cerro Quistvara region. We quickly changed our plans, sorted out a new permit, and headed to a different area: the Miyar Valley. It’s quite popular with European rock climbers, so we found a lot of info about the routes there. But the more information there is and the more developed a valley is, the less room this leaves for a true adventure. Nevertheless, we decided to have a look for ourselves and search for something interesting.

The journey there took three days instead of one. In three days, we could have been on the other side of India, but instead, we were sitting and waiting for the road to be cleared after a mudflow — which, of course, had happened on the very day we set off. Oh well, it could have been worse; we could have been caught in it. We were already starting to think there was something wrong with our karma on this trip—nothing was going according to plan…

It was only on the 11th day that we finally started the trek in. A long journey like that drains your morale, but we tried to keep our spirits up and believe we’d have enough time and a good weather window for a proper climb. As soon as we reached base camp, we started packing for our acclimatisation trip straight away; we didn’t want to waste a single moment.

The girls and I decided to carry all our gear right to the base of the proposed route on the east face of Mahindra. We couldn’t find any information about this mountain being climbed from the east, and the wall looked enticing, with a logical line clearly visible. The approach took us a full day; on the second day, we planned to scout the wall up close and bivy on the pass. Seeing the wall from up close, we tweaked our proposed line slightly, and the route now looked absolutely “banging”. The only thing that worried us was the snowy summit ridge, but for that we had brought some homemade snow anchors made by Zhenya Murin.

So, on the third day, we returned to base camp from our acclimatisation trip full of enthusiasm to climb this wall. It looked well within our capabilities. The only question was how quickly we could climb at 5,000 m, as this was new territory for us — we’d never done technically difficult routes at that altitude before.

After just one rest day, we set off for the route. The next day, we “cast off” and started climbing. We reached our first bivy site a bit later than planned. We’d hoped to fix a few ropes, but we ran out of time. The next day, it started to snow, and it snowed all day. The forecast had promised snow only in two days' time, by which point we had expected to be back down. This snow wasn’t part of our plan, and it stopped us from leaving our bivy site.

Checking the forecast again, we saw they were predicting two to four meters of snow in a day, along with a sharp temperature drop. We realised that at our current pace, we wouldn’t be able to finish the route and get down safely. So, although the decision was incredibly hard, we decided to retreat and abseil down. Something really was wrong with our karma.

We got back to base camp, and the next day the snowfall began. It lasted for four days, but it felt like an eternity. It was like “Groundhog Day”, repeating itself over and over; we lost track of time. The evenings and nights were so cold we bundled up in everything we had. Sometimes at night, you could see the moon and stars, and the whole valley was lit by moonlight, but by morning the endless snow would start again.

We knew that after a snowfall like that, it would take at least 4-5 days for the wall to dry out a bit. And we only had five days left before we had to leave the area.

Naturally, we were burnt out. It felt like we wouldn’t climb anything at all. We were in a kind of stupor after the snowfall. It was hard to motivate ourselves to go anywhere and climb, but sitting around in camp was even more unbearable, so we decided to try a new route on Castle Peak.

When we went to look at the start of our proposed first ascent, we saw water streaming down it, and next to it was a couloir that looked likely to shower us with rockfall. So, we chose a line further left where the rock looked drier. We started climbing, not knowing if it was a first ascent or someone else’s existing line. After a while, it didn’t matter anymore. We were climbing where our eyes led us, and we felt like the true first ascensionists of the wall! It’s an indescribable feeling when you’re not following someone else’s description, but forging your own path — that’s true freedom.

Pitch after pitch, new rock unfolded before us, and we

had to figure out the best way to climb it, trying to avoid using aid and climb

the route as "free” as possible. And we did it! There were a few thrilling

sections we graded around 6c (fr), but otherwise, it was pleasant climbing with

good protection.

We climbed the route with one bivy on the way up and

another on the descent. We’d planned to be faster and get down on the second

day. But we’d underestimated the difficulty of the second bastion with its

ridge and the tower before the summit. We only reached the top around 6 pm, so

we only managed to abseil down to our bivy site. On the morning of the third

day, we continued the descent.

Unfortunately, on the day we got down, the entire base

camp had already been packed up and the horses with all the gear had left. So,

after a morning of abseiling, we were faced with an afternoon 30-kilometre trek

with all our equipment to the nearest village. We stumbled into the village

completely exhausted and dehydrated, but happy that we’d finally climbed

something! Maybe our karma isn’t so bad after all?

In the end, we made a long journey to a peak that wouldn’t have us, then a long journey to a peak that we couldn’t have, and finally, we ascended a peak that gave each of us what we were looking for, whether it was a sense of satisfaction, a sense of overcoming, or a feeling of freedom. I’m thrilled that we managed a beautiful climb, establishing our own line on one of the impressive peaks—Iris Peak in the Miyar Valley in the Indian Himalayas. We climbed the route entirely free, and we did it in an all-female team.

Oksana Kochubey:

A story of an expedition that didn’t go according to plan.

For over six months, we prepared for our expedition to India, obtaining permits, arranging logistics, and planning for every contingency, from bad weather to border delays.

We thought we had everything covered. But as is often the case in the mountains, life reminded us that you can’t plan for everything. We had to be ready to abandon our plan and improvise at a moment’s notice.

Our destination was the state of Jammu and Kashmir, a wild and beautiful region in northern India.

It’s a challenging region, closed for years due to the conflict between India and Pakistan. When the borders briefly opened, climbers flocked there, leading to the legendary ascent of Cerro Kishtwar.

In October 2017, Swiss climbers Stephan Siegrist and Julian Zanker, along with legendary German alpinist Thomas Huber, made the first ascent of the northwest face of Cerro Kishtwar (6,155 meters).

After that, Kishtwar opened and closed sporadically, as if the mountain itself were deciding who to welcome.

The area had been open to foreign climbers for the past few years, and we were hopeful. But fate intervened. In April, just before our trip, another clash between India and Pakistan led to the region’s closure after several tourists were killed.

Our outfitter kept assuring us, “By September, everything will be fine. The area will reopen, and you can go without worry.”

But it didn’t happen.

Mountaineering in India is organized differently than in Russia. First, every ascent requires a permit for the specific peak you plan to climb. Second, each foreign expedition is assigned a liaison officer, for whom you must provide accommodation, food, and transportation.

You can’t arrange this independently. Regulations require hiring a local company to handle logistics, daily needs, and support for the liaison officer. A cook is also typically included with the liaison officer.

The silver lining? After a long day in the mountains, a hot meal from a local chef made up for the lack of a hotel and boosted our morale.

Upon reaching Kishtwar, we encountered an unexpected obstacle: the local police department denied us passage. The official reason was a recent, powerful landslide that had closed the area to tourists.

Honestly, it felt like an excuse. The local authorities seemed worried that something more serious than a rockfall might happen, especially with Russian mountaineers in the area. Still, our team wouldn’t give up. We gathered our courage and met with the head of the local administration, and then the chief of police.

We secured a personal appointment and explained how long and carefully we had prepared, and how important it was for us to reach this area. But the police chief was unmoved. He listened, nodded, and said flatly, “Come back in 2029.”

Those words were a death sentence. We were beyond disappointed. But in the mountains, you learn to accept reality. If one path is closed, you find another.

We spent hours, then days, searching for a new region and potential peaks, poring over the American Alpine Journal. The most realistic option was the Miyar Valley, a stunning, largely unexplored region with countless side gorges. Some peaks there had been explored by European teams, so we could count on some information and established routes.

We quickly got new permits and set off. The journey normally takes six to eight hours, but for us, it stretched into three days. September in India is the season for mudslides. Mountain roads are often closed for debris clearing.

We were unlucky. On the day of our journey, a mudslide blocked the road with huge boulders, and it took nearly three days to clear.

By the time we moved on, we were exhausted. We were losing time and hope. And yet, we reached the valley. In total, we lost eleven days. From there, it was a ten-hour hike to base camp.

Horses accompanied us to base camp — eleven in total, which was more than usual. Even with a basic logistics package, the outfitter provided a dining tent, toilets, a shower, and plenty of food— not exactly light provisions

To save time, we decided to do the entire thirty-kilometer trek of rocks, trails, and rivers in one day. It wasn’t easy, but we were driven by the desire to finally start our expedition.

We deliberately chose a campsite at the foot of Castle Peak, the symbol of the valley.

Its massive, distant wall set the tone for the landscape: austere, monumental, and mesmerizingly beautiful.

We reached base camp late at night, exhausted but content. We quickly pitched our tents, ate, and fell asleep, with many plans and little strength for the days ahead.

In the morning, under the soft sunlight, we met and split into three teams to acclimatize and scout routes in different gorges.

We spent four days in constant motion. Andrey Panov and I covered over seventy kilometers, exploring the region’s most remote valleys.

Each team returned with a good haul. The women and I chose to climb the east face of Mahindra, a slender, majestic peak over six thousand meters high. Its line captivated us: elegant, clean, and logical — the kind you want to climb the moment you see it.

A powerful snowstorm was forecasted, with up to 120 centimeters of snow expected by the end of the week. We had three days and were ready to push our limits.

From the start, we felt our lack of acclimatization. We had too much gear and hadn’t recovered from the long journey and reconnaissance.

We climbed seven pitches the first day and planned to fix four more on the second.

Everything was going to plan until unexpected snow arrived in the morning. The forecast had promised no precipitation, but the wall was icing over, our clothes were soaked, and our spirits sank. The updated forecast was unbelievable: up to three meters of snow in two days!

We faced another difficult choice. Reason told us to descend. Three meters of snow in a day would mean maximum avalanche risk. A helicopter couldn’t fly, and even descending to base camp on our own could become impossible. But a stubborn part of us refused to retreat, dreaming of pushing on to the summit and a new altitude record.

In the end, reason won. We began our descent the next day, feeling we had made the right decision.

An unfinished line on the eastern face of Mahindra

The bad weather persisted for four days. So much snow fell that our chances of returning to the original route vanished. Time seemed to stretch on endlessly.

During the day, we dug out the tents, read, and exercised. In the evenings, we gathered in the dining tent to play cards, roll dice, and joke around. The games lasted late into the night. When everyone went to bed, a cosmic silence fell. The moon lit the snow-covered mountains, and snowflakes drifted down, suspending the world between reality and a dream.

Every morning, we looked at the slopes, hoping to see rocks and earth, but everything was still blanketed in white.

We knew we couldn’t reach the distant valleys. Too much snow, too little time. Our last chance was to climb Iris Peak, one of the most beautiful peaks of the Castle massif.

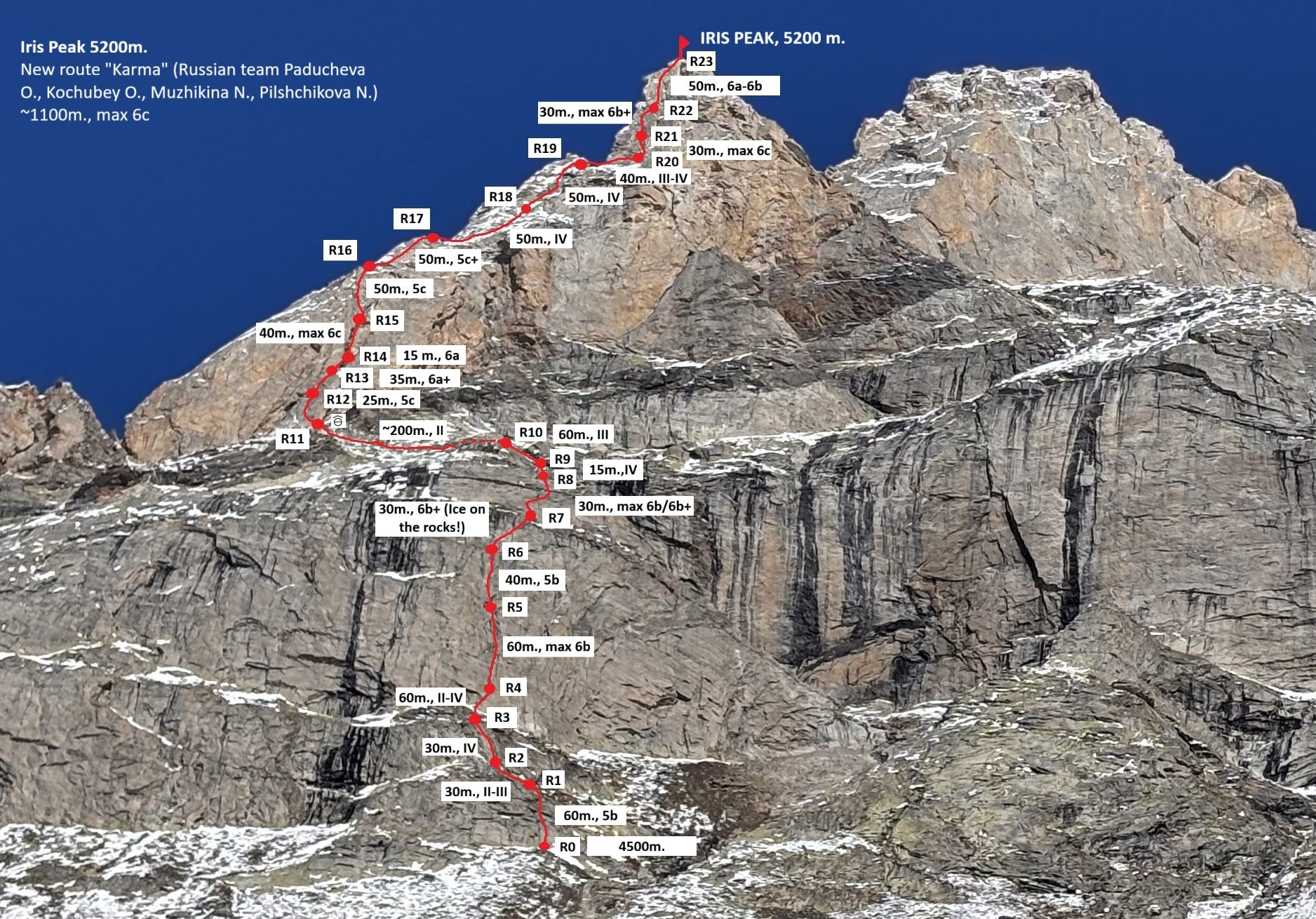

Several routes had been climbed on this peak, but the line that captivated us was unclimbed. With its three massive rock bastions, a route of about a thousand meters, and a height of over five thousand meters, it was a worthy challenge for our team.

We decided to travel as light as possible: less gear, less food. We even left our ice axes behind for the sake of speed. It was a risky decision. In the mornings and evenings, the rock was coated with ice, making the hanging belays treacherous. The snow on the ledges crusted over, and one of our team members nearly fell. Fortunately, a quick reaction arrested the fall.

We planned for one bivouac, taking only snacks and four packs of instant noodles. Luckily, we brought a full gas canister, as the mountain was more serious than it looked.

After the first bastion, we faced a huge gap; after the second, a snowy ridge; and just below the summit, slippery slabs. We climbed the route “clean” (without aid), but the leader had an adrenaline-filled time with wet cornices, icy rocks, and questionable protection.

The sun was a welcome sight during the day, but it disappeared quickly, taking the warmth with it.

The route’s length, altitude, and difficulty slowed our pace. On the first day, we only climbed the first bastion. There was no flat ledge for a tent, just a rocky, sloping, snow-covered incline where we sank to our waists. Our experience on the Ullun expedition helped: Olya and I built a decent ledge. Meanwhile, the two Nadias fixed a couple of ropes before dark.

We had overestimated our strength or underestimated the route. We had planned to summit and descend to base camp by evening, but the second bastion was iced over, the ridge was treacherous, and the summit was formidable.

On the second day, each of us battled our own demons. Olya pushed on with her last bit of strength. The cold and altitude had drained us. The rest of us jumared, untangled ropes, and gave it our all. At one point, I realized how much we had underestimated the route’s length and considered turning back. But in the mountains, a team is a single organism. Decisions are made collectively. We knew fatigue is dangerous; it dulls your attention, and a single mistake can be catastrophic.

We were experienced mountaineers and knew not to let our guard down. We pushed on, each with our own fears and pain, but united as a team.

We reached the summit at 6:10 PM, a little earlier than our Ushba climb, and we all agreed it was a success.

After sunset, the temperature dropped to -20°C. Staying on the summit was reckless, but night rappels were also dangerous. We moved cautiously, double-checking every anchor. When a rope got stuck, Nadia P. volunteered to retrieve it. She later admitted she was close to tears at the thought of jumaring 60 meters up after such a grueling day.

By midnight, we were back at the tent. After a five-hour descent, our reward was hot water, leftover snacks, and sleep.

We confirmed by satellite that base camp would be packed up in the morning, the horses would leave, and our non-refundable transfer to Delhi was scheduled. We still had about 10 rappels to go. We realized the work wouldn’t end there. We’d have to carry all our gear 30 kilometers back to the village, mostly in the dark. We accepted it calmly. Karma is karma. A little hungry, we went to sleep.

Morning rappels are a better wake-up call than coffee. Even with only four hours of sleep, you can’t rest at an anchor: the rock is icy, your hands and feet are frozen, and the ropes tangle. We had damaged the rope during the night and only noticed it in the morning. We cut off the damaged fifteen-meter section, which became a useful spare.

The descent took five hours, plus another hour and a half to the former base camp. The place was empty. The horses had already left with everything they could carry.

Andrei and Ilya were waiting for us. They had prepared a celebratory feast with the leftover food and gas. We hadn’t eaten in almost a day and devoured everything.

The horses had left only half an hour earlier. It was frustrating, but we rested, packed our gear, and continued to the village. The trail was barely visible: mud, snow, and wet grass. We didn’t want to walk in our double boots, so we accepted that our sneakers would be soaked in minutes.

We came to a ford. The water was waist-deep, and the current was so strong that we had to cross in pairs, holding on to each other. The water was shallower but much colder. We summoned our courage, stripped to our underwear, and stepped into the icy stream. Our legs cramped, but a few minutes later, we were on the other side, laughing and trying to warm up.

The thirty-kilometer trek after such a climb was grueling. As Nadezhda M. put it, “Giving birth was easier!” By the end, our legs were tangled, our backs ached, our knees throbbed, and we just wanted to collapse.

The journey took about nine hours. We wouldn’t have made it without the team’s support. Ilya was our “guiding star”, setting the pace and navigating, while Andrey kept our spirits up with jokes and encouragement.

Weeks after the expedition, I still mentally relive it, reflecting on the trials, the restarts, and the search for strength and inspiration. The most important thing is that we kept our team spirit, sense of humor, and ability to accept whatever came our way. I’m proud of my team and so happy that, against all odds, we traveled to India, reached the mountains, and established our own women’s route in the Indian Himalayas. This is our Karma.

Our expedition was made possible by our friends and partners. We thank them for their support and faith in our team.

Women’s mountaineering in Russia

И снится нам не рокот камнепадов, а… тропинка в Севастополь

Nominee 2025: Sourire Kirghize route. Free Climbing in Karavshin

Karavshin. Where Dreams Come True

Open Alpine Cup between an all-female team in the Caucasus

The First All-Female Ascent on Chegem Peak’s NE Face via Forostyan Route, 6A

Ася Кукушкина и Даша Ковалева прошли маршрут Горина 5А на Цей-Лоам

Маршрут Андреева 5А на Коазой-Лоам свободным лазаньем

Женская команда из Воронежа прошла маршрут Горина 5А на Цей-Лоам

Perestroyka Crack свободным лазаньем

First ascent of 4818 Peak

Зима, февраль. Северная стена Бокса

Short-list «Стального Ангела-2023». 5 Б на Далар и гроза на спуске