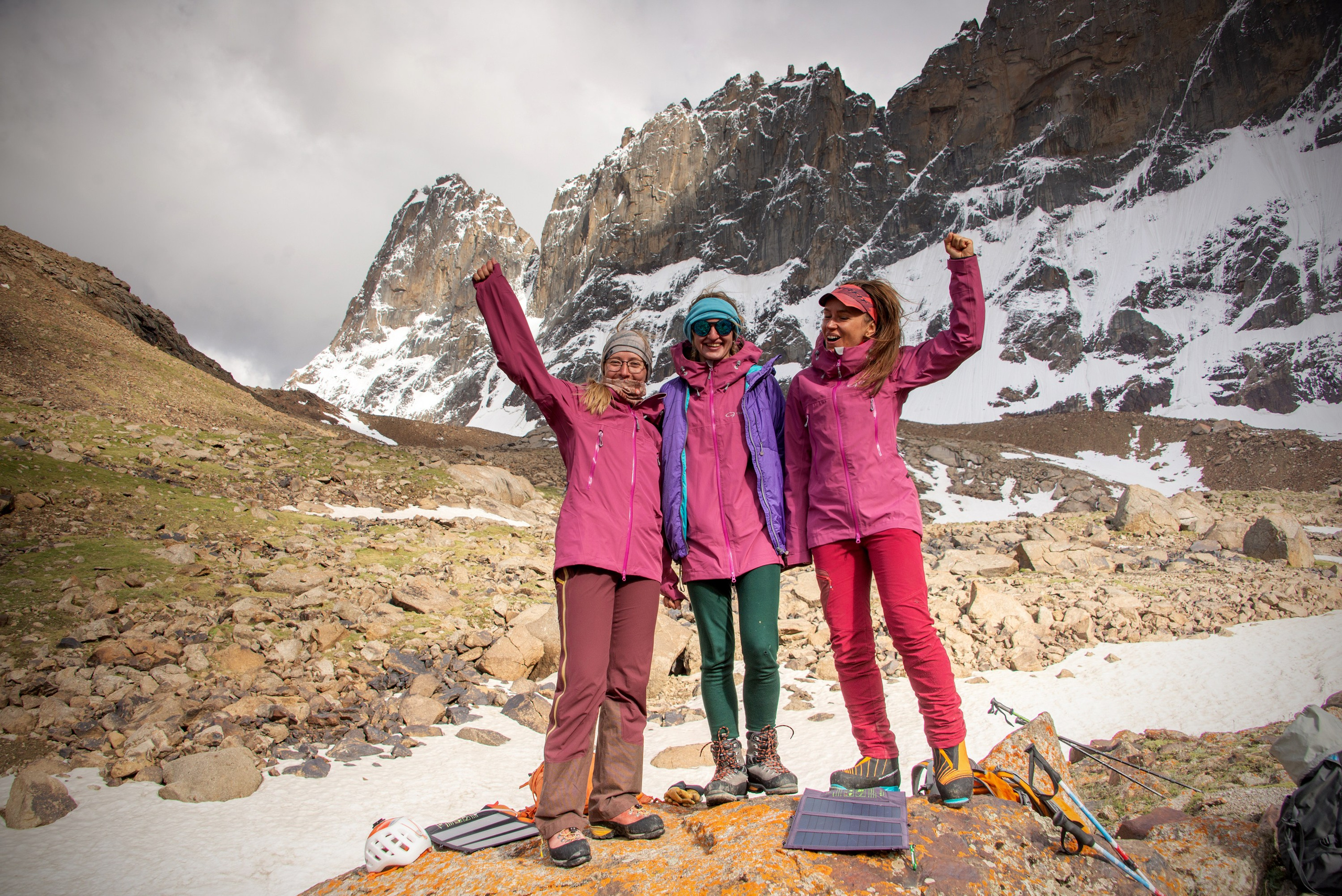

The all-female team of Steel Angel award winners—the Russian equivalent of the Piolet d’Or for women—Olga Lukashenko, Anastasia Kozlova, and Darya Serupova, established two new beautiful daring routes on the sheer granite faces of the demanding walls in the remote Sabakh Valley.

This journey was supported by the Grit& Rock Expedition grant, which aims to promote and support women climbers embarking on first ascents, new routes and exploratory adventures.

Olga Lukashenko

Steel Angel award winner (2019, 2023).

Multiple-time winner of various mountaineering competitions, a mountain rescuer, and an IFMGA aspirant guide.

Member of the Russian national mountaineering team.

Daria Seryupova

Steel Angel award winner (2022).

A dedicated 8a rock climber. Multiple-time winner of the Russian rock climbing championships.

Member of the Russian national mountaineering team.

Anastasia Kozlova

Steel Angel award winner (2022).

A distinguished multiple medalist in rock climbing championships and stages of the Russian Cup in both rock climbing and mountaineering.

Member of the Russian national mountaineering team.

First ascent of the North Face of Argo Peak (4750m) completed by an all-female team:

ED, R29 pitches, 1250m, 7b, А3+, M6

The Sabakh region is a rugged and isolated area, offering a wealth of untapped first ascents. Yet, despite its vast potential, only a handful of daring expeditions have ventured into this remote landscape, dominated by towering granite walls. Historically, these daunting ascents were the domain of the strongest male teams. However, in a historic first, a female team has now completed the ascent of the Ashat Wall, marking a new chapter in the valley’s climbing legacy.

The first part of the route primarily consists of mixed climbing up to M6, with snow-ice slopes, ice-filled cracks, and loose rock. The second part becomes steeper and more rocky with climbing pitches up to 7b, though ice-filled cracks remain a challenge.

Additional difficulties included rockfall hazards, along with predominantly harsh weather conditions: snow, fog, hail, and thunderstorms.

The ascent to the summit took four days, with an additional full day for the descent. There are no good bivouac spots on the wall, so we used a ledge platform.

First ascent of the Southwest Face of Parus Peak (4850m), ED-

Length 1440m, elevation gain 1150m, R28, 6c, А2, M3

To acclimatize and warm up, the team completed another first ascent — of Western Parus Peak via the Southwest Face (4850m).

Olga Lukashenko:

I’ve long been captivated by the idea of climbing the north face of the formidable Sabah, the crown jewel of the Ashat Wall. Over the years, I’ve amassed a collection of splendid blunders, and I count myself fortunate that this particular escapade didn’t add another to the list. Wisely, we decided to give the treacherous, avalanche-prone Sabakh a wide berth. Instead, we set our sights on the equally beautiful but decidedly less perilous West Parus and Argo peaks.

The logistics of this expedition were an adventure all their own. First, we hopped on a plane to Osh, a vibrant city teeming with people and cows, with a bustling marketplace that never seems to stop. From there, we embarked on a full day’s journey by road to the village of Ozgurush. Upon arrival, we loaded 200kg of equipment and provisions onto donkeys and horses, and the real fun began—a two-day hike through rugged terrain. There was a unique thrill in knowing we were entirely on our own during this autonomous expedition—two days' hike from the nearest settlement, with just the four of us: the rope team and our coach.

When we finally reached the valley, the mountains were draped in fresh snow. We waited patiently for two days, giving the face a chance to shed its new icy cloak. We set up our base camp about 2-3 hours from the Ashat Wall, conveniently near a reliable water source. Our ABC was just a 40-minute trek away, making it the ideal staging ground for our climb of Argo, our main objective.

West Parus (ED-, 28 pitches, 1460m length, 1150m elevation gain, 6c, M3, A2).

When we arrived in the valley, the mountains were buried under fresh, heavy snowfall. For two days, we waited patiently, giving the face time to shed its new mantle of snow.

To acclimatize and warm up, we decided to draw a nice, logical line up a giant dihedral of the “rocky” West Parus. The terrain looked promising, with beautiful rock climbing pitches involving friction climbing. We were confidently making progress, but it soon became clear that our so-called “rocky” Parus wasn’t as rocky as advertised. The final sections were packed with snow and ice, which obviously meant mixed climbing. Without tools or crampons (which we simply didn’t bring with us from BC), I found myself climbing ice and mixed terrain with a rock hammer for the first time ever, occasionally using it to chop steps. This was either incredibly innovative climbing or nod to the early climbing trailblazers, but definitely not a lack of planning or foresight. I’m not sure I’m keen to repeat it, but hey, it was certainly an interesting experience!

We bivouacked once midway up the wall (sitting on our packs and neatly laying out the rope to provide as much cover from the ground as possible) and once near the summit.

Argo (ED, 29 pitches, 1250m length, 950m elevation gain, 7b, M5, А3+)

Finally, the big day has arrived! Once again amazed by the size of the Argo, we figured the only spot where you couldn’t see its intimidating wall was from the wall itself, so we started climbing up!

We kicked off through an ice gully, but by day five, when we were rappelling down, it had completely melted away. The warm temperatures made the ice conditions unstable, with entire sections of rock and ice breaking off without warning. With everything so sketchy, I opted for not very steep but technical mixed climbing, even though the ice gullies would’ve been quicker and easier. The three screws I’d placed in the rotten, spring ice were just for my own sanity. Nevertheless, we managed to climb the first 500 meters of vertical gain—nearly half the route—quite quickly, completing it in one day.

The second half of the wall became significantly steeper. The main challenges? Oh, just slippery, ice-filled cracks, loose rock, rockfall hazards, and weather that seemed to think it was auditioning for a disaster movie—constant thunderstorms, hail, and snow kept us on our toes. To top it off, we had to haul heavy equipment up the mountain, which turned out to be a real endurance test we somehow miraculously passed. And let’s not forget the well-worn portaledge that flatly refused to cooperate, and was clearly designed to test our willpower and sense of humor. Otherwise, watching us wrestle to assemble it for two hours daily would have been unbearable.

The following day, with a storm and poor weather forecast, our plan was to ride out the storm but still make some progress. While my two climbing partners battled through a few pitches, the sky darkened and hail and snow began. I remained in the portaledge, feeling a pang of jealousy. I ate everything I could reach and kept rolling from side to side to appear occupied.

The next two days of climbing were intense, pushing us to 7b in french grades. Nastya tackled an incredible frozen chimney with fearless precision. Dasha encountered a stunning crack stretching several pitches, which ideally required a #6 Camalot, but with only a #4 in our gear, every placement turned into a thrilling exercise in creativity. I faced a demanding aid section up to A3+, characterized by vertical, disconnected blocks. In these sections, removing a single piece of protection could trigger a cascade of failures and even damage the rope. We were immensely relieved to have navigated what could have been an insurmountable obstacle. As Mark Twight famously said, “It doesn’t have to be fun to be fun.

Each step brought us closer to our long-awaited bivy on the shoulder, and the excitement was palpable. We had decided to go light for the summit push, leaving behind the portaledge, sleeping bags, and other gear at the bivy. The route featured several pitches of enjoyable climbing, pillars of granite, interspersed with some simul-climbing. After four more pitches, we finally reached the summit.

Rappelling down went smoothly! The rope didn’t get stuck even once. There were many free-hanging descents, which, with heavy backpacks, turned into excellent exercises for the core and back muscles.

On the last pitch during our descent, we unclipped the portaledge and watched as it limply bounced and rolled down the slope. The three of us relished the spectacle, savoring the blissful moment of sweet revenge!

Delighted yet physically drained, and recalling our lively debates—such as whether to rappel down on the first day or to ambitiously aim for the summit first—we finally did it! After five intense days (four climbing up and one descending), we established this beautiful, daring new route on this challenging and demanding north wall.

Returning to base camp after five days on the Ashat Wall felt like coming back after months. It had been such an epic adventure. I have no doubt that these are landmark new routes for the three of us, and we’ll remember this trip as a significant turning point for a long time to come. As for where this turning point will lead us, well, we’ll see.

День 4

Лезем финальные скальные участки. Здесь обещают простую логистикой, надо просто тараканить вверх несколько веревок по широкой щели под 6й камалот. Даша очень рада этой новости, зная, что максимальный размер кама, который у нас в наличии — четверка, и то одна. Внутри скальные пробки, они спасают. А мне просто всегда приятно смотреть на скалолаза 8а, в любых кондициях.

О, да, мы на перемычке! Открывается потрясающий, первозданный вид на снежные пики Таджикистана. Шикарный подарок, очень красиво. Километровые кыргызские стены с этой стороны совсем коротенькие. Дальше по гребню топаем на вершину. Черт, какое счастье.

День 5

Просто и коротко — дюльфера прошли обалденно! Да, мы перебили одну из веревок, да, мы часто дюльферяли с одного якоря (Даша — мой герой), неделю назад поклявшись — ни-ни, но все прошло просто как по маслу, веревка ни разу нигде не застряла — еще один прекрасный подарок.

Уже на снегу после берга Настя отстегивает платформу, и мы все втроем завороженно со сладким чувством упоения вендетты смотрим, как она, безвольно подпрыгивая, катиться вниз. Садистская радость!

Это все было и это все закончилось. Акцент на «было», на том, что это состоялось. У меня реально нет никаких сомнений, что это знаковые для нас троих первопроходы и мы все запомним этот трип как поворотную точку надолго. Поворот куда? Узнаем ;)

Спасибо огромное Дэнику Прокофьеву — без тебя этого бы просто не было, Марине Поповой — за то, что ты это ты, и за постоянную связь с нами и большим миром. И всем, кто помогал словом и делом, кормил, переживал, ждал.

Спасибо компании Венто за снаряжение, O3 Ozone за отличные мембраны, Julbo за очки, Grit& Rock Expedition Award за финансовую поддержку, премию Стальной ангел и Mountain.RU за инфоподдержку. До скорого!

Women’s mountaineering in Russia

Ася Кукушкина и Даша Ковалева прошли маршрут Горина 5А на Цей-Лоам

Маршрут Андреева 5А на Коазой-Лоам свободным лазаньем

Женская команда из Воронежа прошла маршрут Горина 5А на Цей-Лоам

Perestroyka Crack свободным лазаньем

First ascent of 4818 Peak

Зима, февраль. Северная стена Бокса

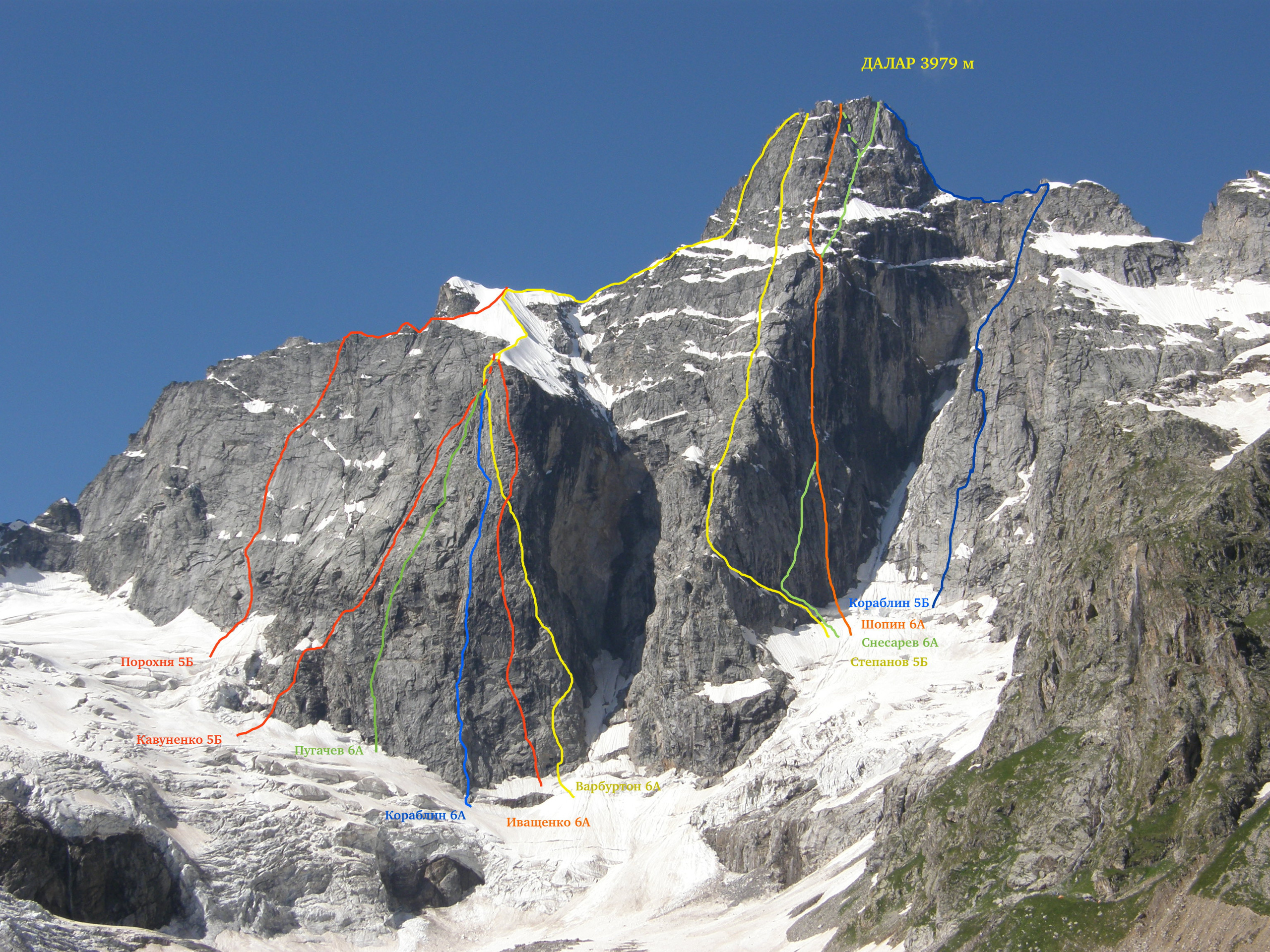

Short-list «Стального Ангела-2023». 5 Б на Далар и гроза на спуске

Short-list «Стального Ангела-2023» — Каравшин. 6А на пик 4810

Short-list «Стального Ангела-2023». Каравшин, пик Асан, маршрут Горбенко, 5Б

Лонг-лист «Стального ангела» — 2022. Трио в тройке

Лонг-лист «Стального ангела» — 2022. Питер на Шоколадном

Женская тройка прошла маршрут 5Б на Далар в Узунколе

Женская команда Ростов-Воронеж. Восхождение выходного дня

Лонг-лист «Стального ангела» — 2022. Новое поколение 3D